Why do you make Hornbooks? Largely because I'm a history student. Hornbooks represent America's first school text "books". Long before the Battledore, the Chap Book, the McGuffy Reader - there was the Hornbook. The tradition came over from Old World Europe, where these devices date to the middle ages. They represent Old World artisan-ship from a time when things were made by hand, one at a time.

Are your Hornbooks for sale? Yes. While usually a "batch", or production run is the result of an order or several orders, there are usually some left over which are available. If enough orders are requested, I'll double the batch. More than likely sixteen would be about the maximum number that I can produce at one "run". That would represent about two weeks production time.

All Hornbooks are priced at $35.00 plus $5.35 for shipping. (Price updated 11.3.2013 due to increase cost and Flat Rate shipping.)

Orders can be placed by posting an e-mail to me at: paperwrenpress@gmail.com

Pmt can be made by personal check or PayPal. Please note that PayPal incurs a $2.00 charge for use of their service, thus total for Hornbook and shipping via PayPal is $42.35

(update 9/27/2014: Coming Soon! look for Hornbooks to be offered from Paper Wren Press' Etsy Shop! These will be linked from our website at www.paperwrenpress.com )

Are your Hornbooks a specific copy of any particular specimen? No. The local printers of the 1600's or 1700s - printers did not proliferate in the Americas until the very early 1700s - followed a familiar Old World pattern which was traditionally used. It was more of a format with variations unique to each printing house, and dependend upon what "founts" and cuts were available to them. Almost all followed the tradition of the "Criss Cross", the "Cross Row" of the lower case alphabet. Most started the lower case row with the cross and upper case A, followed by the lower case alphabet. Nearly all utilised the Exorcism ('in the Name of the Father . . .' ) and the Lord's Prayer. The fonts used, point size, the types of crosses or the number of crosses varied. Some used borders, some did not. If I were a printer in 1730, and I was asked to print a few Hornbook pages for the local artisans cutting the wood and heating the horn, these are what I would have produced, proudly displaying the brand new Caslon faces from England. I probably would not have had a superabundance of type available, so I would have distributed the type back into their cases when I was done. So the next time I was asked, the Hornbook would have looked a little different.

Photos of originals show a sort of frame around the printed sheet on most Hornbooks. Why is that? Yes, and you'll notice mine do not. Those old Hornbooks actually used animal horn as a protective covering for the printed page affixed to the board. This thin piece of heated, smoothed and cut horn was held in place by what was usually a lead frame. There are two issues here: the lead and the horn. You might note from the photos on line and in books that the horn is usually missing. Or very deteriorated. Horn is organic and is subject to rot. I chose not to use a frame simply because of the modern day fear of lead. Especially since these Hornbooks may - as their predecessors - find their way into the hands of kids. Museum or private gift shops may have a problem with the use of lead, too. I opted instead to use another form of protection which, though not as ancient as cut horn, still goes back about a century and a half: decoupage. There are several techniques used for this process, originally layers of varnish which were dried and sanded. I use a water based sealant, each thin layer polished with steel wool, the last coating cured for a few days, then sanded and polished by steel wool. The water based sealant does not adversely affect the paper, and is extremely durable. This last batch utilised copper tacks to hold the paper in place. There are examples of Hornbooks that do not use frames, thus the use of frames to hold the horn was not universal. Personally, I think the Hornbook looks better without a frame, which tended too be too large for the diminutive size of the book itself.

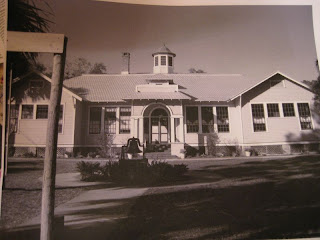

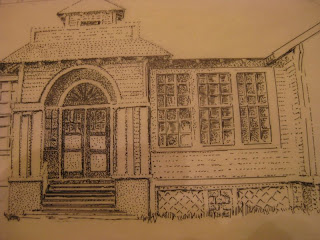

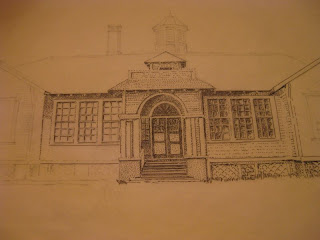

Who buys Hornbooks these days? So far, it's been a matter of letting folks know what a Hornbook even is! What used to be a ubiquitous part of childhood has now slipped from social memory. So far, Museums, folks who like Colonial and Early American accents for their homes, Home Schoolers and some private schools have been interested or have placed orders. Although, admittedly, I don't ask. But the niche market I am aiming at would be the above. The gift shop attached to the Oldest Schoolhouse in Old St. Augustine, Fl. has expressed interest in carrying these Hornbooks. Thus, as folks become aware of the Hornbook, I suspect more folks may wish to have one. The chalk-and-slate board of your great grandfather would have been the "Hornbook" of it's era. Both carry the same early schooltime aura and legacy. Heh, just thinking about it, I used a slate and chalk pencils made by Pelikan when I went to primary school in Germany in the middle 1960s! The slate was ruled on one side, quadrille on the other. That's where I got my history-streak!

Hope this page has been a little more point specific and helpful.

Good Providence in all your endeavours!

-gary

Are your Hornbooks for sale? Yes. While usually a "batch", or production run is the result of an order or several orders, there are usually some left over which are available. If enough orders are requested, I'll double the batch. More than likely sixteen would be about the maximum number that I can produce at one "run". That would represent about two weeks production time.

All Hornbooks are priced at $35.00 plus $5.35 for shipping. (Price updated 11.3.2013 due to increase cost and Flat Rate shipping.)

Orders can be placed by posting an e-mail to me at: paperwrenpress@gmail.com

Pmt can be made by personal check or PayPal. Please note that PayPal incurs a $2.00 charge for use of their service, thus total for Hornbook and shipping via PayPal is $42.35

(update 9/27/2014: Coming Soon! look for Hornbooks to be offered from Paper Wren Press' Etsy Shop! These will be linked from our website at www.paperwrenpress.com )

Are your Hornbooks a specific copy of any particular specimen? No. The local printers of the 1600's or 1700s - printers did not proliferate in the Americas until the very early 1700s - followed a familiar Old World pattern which was traditionally used. It was more of a format with variations unique to each printing house, and dependend upon what "founts" and cuts were available to them. Almost all followed the tradition of the "Criss Cross", the "Cross Row" of the lower case alphabet. Most started the lower case row with the cross and upper case A, followed by the lower case alphabet. Nearly all utilised the Exorcism ('in the Name of the Father . . .' ) and the Lord's Prayer. The fonts used, point size, the types of crosses or the number of crosses varied. Some used borders, some did not. If I were a printer in 1730, and I was asked to print a few Hornbook pages for the local artisans cutting the wood and heating the horn, these are what I would have produced, proudly displaying the brand new Caslon faces from England. I probably would not have had a superabundance of type available, so I would have distributed the type back into their cases when I was done. So the next time I was asked, the Hornbook would have looked a little different.

Photos of originals show a sort of frame around the printed sheet on most Hornbooks. Why is that? Yes, and you'll notice mine do not. Those old Hornbooks actually used animal horn as a protective covering for the printed page affixed to the board. This thin piece of heated, smoothed and cut horn was held in place by what was usually a lead frame. There are two issues here: the lead and the horn. You might note from the photos on line and in books that the horn is usually missing. Or very deteriorated. Horn is organic and is subject to rot. I chose not to use a frame simply because of the modern day fear of lead. Especially since these Hornbooks may - as their predecessors - find their way into the hands of kids. Museum or private gift shops may have a problem with the use of lead, too. I opted instead to use another form of protection which, though not as ancient as cut horn, still goes back about a century and a half: decoupage. There are several techniques used for this process, originally layers of varnish which were dried and sanded. I use a water based sealant, each thin layer polished with steel wool, the last coating cured for a few days, then sanded and polished by steel wool. The water based sealant does not adversely affect the paper, and is extremely durable. This last batch utilised copper tacks to hold the paper in place. There are examples of Hornbooks that do not use frames, thus the use of frames to hold the horn was not universal. Personally, I think the Hornbook looks better without a frame, which tended too be too large for the diminutive size of the book itself.

Who buys Hornbooks these days? So far, it's been a matter of letting folks know what a Hornbook even is! What used to be a ubiquitous part of childhood has now slipped from social memory. So far, Museums, folks who like Colonial and Early American accents for their homes, Home Schoolers and some private schools have been interested or have placed orders. Although, admittedly, I don't ask. But the niche market I am aiming at would be the above. The gift shop attached to the Oldest Schoolhouse in Old St. Augustine, Fl. has expressed interest in carrying these Hornbooks. Thus, as folks become aware of the Hornbook, I suspect more folks may wish to have one. The chalk-and-slate board of your great grandfather would have been the "Hornbook" of it's era. Both carry the same early schooltime aura and legacy. Heh, just thinking about it, I used a slate and chalk pencils made by Pelikan when I went to primary school in Germany in the middle 1960s! The slate was ruled on one side, quadrille on the other. That's where I got my history-streak!

Hope this page has been a little more point specific and helpful.

Good Providence in all your endeavours!

-gary